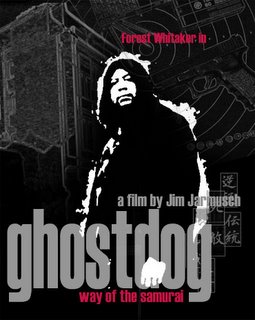

In the past fews days I read Zen and War by Brian Victoria, a Soto Zen priest aghast at the complicity of the Buddhist priesthood in Japan with their rulers' warmongering from the beginning of the Meiji restoration through their defeat and subjugation at the end of WWII. In a semi-lucky confluence, I also saw Jim Jarmusch's Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, a 1999 film starring Forest Whitaker as an inner-city killer for hire whose absolute adherence to the code of Bushido leads him to become"retainer" to a mobster, with tragic consequences. Combined, the two show us (1) the absolute and empowering nature of Zen practice, and (2) the fact that it takes us more than zazen to know how to choose our path in our social setting, whatever that may be.

In the past fews days I read Zen and War by Brian Victoria, a Soto Zen priest aghast at the complicity of the Buddhist priesthood in Japan with their rulers' warmongering from the beginning of the Meiji restoration through their defeat and subjugation at the end of WWII. In a semi-lucky confluence, I also saw Jim Jarmusch's Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, a 1999 film starring Forest Whitaker as an inner-city killer for hire whose absolute adherence to the code of Bushido leads him to become"retainer" to a mobster, with tragic consequences. Combined, the two show us (1) the absolute and empowering nature of Zen practice, and (2) the fact that it takes us more than zazen to know how to choose our path in our social setting, whatever that may be.Zen at War (Weatherhill, 1997) was written by a Soto priest trying to deal with the legacy of deceit and dishonor left by the Zen establishment, and the Japanese Buddhist establishment in general, at the close of the Second World War. The book provides no biographical background for author Victoria; I hope at some point to encounter more of his personal story. From what little I know of Japanese society, it appears that the post-War generations know little of the mechanics of how their society was led to disaster by the process leading up to 1945. So I suspect that Mr. Victoria was shocked at some point to discover that his adopted faith (and I garner from his name that he is not Japanese), which in modern times has been a voice for peace, was so recently an instigator of a terrible war.

Mr. Victoria's book is a painstakingly researched account of how Buddhism became Imperial Buddhism, and of how it has attempted (or refused) since then, to cope with disaster and embarrasment. To summarize at the risk of misstatement, Zen entered Japan from China around 600 B.C. and with its adoption by Prince Shotoku (sort of the Emperor Constantine of Japanese Buddhism) merged into feudal society where it melded with Bushido, the code of the warrior. Zen, with its emphasis on focused mind and living in the moment, was perfect for sword training. With its lack of a governing deity to provide moral laws and allegiance, it was easily co-opted by the ruling class, and after 1600 became the religion of the Samurai and the Shogunate, co-existing and blending with the Shinto of the people. However by the beginning of the Meiji restoration in 1868, it had become a shell of itself, focused heavily on ancestor worship and coming to the fore mostly at funerals.

The existence of War-Whore Zen seems to have emerged as an accomodation of the growing Japanese equivalent of Manifest Destiny, flowering in Japan's wars with China in 1894 and with Russia in 1905. The book documents which Buddhist leaders (and the other sects, like Tendai and Jodo) did, said, and published what, in their efforts to out-lick each others' boots in support of Imperial Japanese aggression, culminating in World War II. While it is easy to excuse the teachings which came out of Japanese Buddhism in that period as efforts to survive in a wartime society with no history of free speech or of tolerance to political resistance, it is clear that the Buddhist leaders went way, way over this line.

The most stunning message of this book, however, comes with the realization that the peaceful Buddhist leaders of our era are the direct disciples of leaders who for the most part either never apologized at all or did so half-heartedly. If you want to trace your own lineage for such horror, the book provides the means to do so. Suffice it to say that recognized icons of the foundations of American Zen like D.T. Suzuki, and the religious progenitors of Philip Kapleau, were among the worst offenders. Even the most (relatively) abject apologies stop short of saying that war is wrong, and there is a maddening thread of insistence that twentieth century Japanese expansionism was in some way conducted for the benefit of the peoples of Asia.

Ghost Dog is the story of an inner-city Black man who, in his youth, is rescued from a gang of attackers by a third-rate Mafioso. It is never revealed how Ghost Dog comes by his obsession with Bushido, but its message of subjugation to the ruler becomes an attachment to his rescuer which leads him, in combination with his weapons training and high-tech skills. Ghost Dog lives on a ghetto rooftop from which he communicates with his mob boss by passenger pigeon. He is reverend and left alone by the gangs that run his neighborhood. Jarmusch was perhaps wisely omitted how Ghost Dog came by his creed, let alone his skills and hardware; I think our credulity is strained enough. But the character is beautiful. Ghost Dog carries a copy of Hagakure - The Book of the Samurai, from which the films's frequently posted aphorisms derive. He befriends a young girl and gives her a copy of Rashomon, opening to her the door to his adopted culture.

The film itself is a classic tragedy, in that the heroe's flaw - in this case, the fact that his code of honor not only leads but obligates him to attach himself to an unfit and unsuitable ruler, the mobster - lead to his undoing. Since I strongly encourage you to see the film if you haven't already, I won't spoil the ending any more than I have. I also have to note that the word Zen is used sparingly in the movie, if at all, although Ghost Dog is depicted several times doing an incongruosly sloppy zazen. But to me, seen in conjunction with the book, the message is that the incredibly powerful nature of Zen practice and its concommitment lack of attachment to outside codes of ethics, lead to a danger of misdirection which can lead to the strength gained by the empowerment of the practice, being used to very wrong ends.

A couple of points have to be made in qualification. The sutras say very little about war. The conjugation of Zen and Bushido is to some extent an accident of history, although one to which Zen is open by its nature. It would appear to me to be a huge error to say that practitioners of Zen are more open to led into "incorrect action" by their "faith" or practice than, say, Christians or Moslems, which historically have much more to account for in terms of misdirected aggression than Buddhists. But as the Zen complicity of this century shows, when they go wrong, boy, they do it in a big way.

I guess my point here is that, as I've been saying, don't get your politics from the guy who teaches you zazen or encourages you to do it, even if it's me. That's a decision you have to make for yourself, and you owe it to yourself to be as informed as you can before you make it. There are people whose every comment on Zen practice I've found through my own experience to be not only helpful, but true, but whose beliefs on the issues facing the world today are naive beyond my comprehension. Zen practicewill enable to become more of who you are, and will enable you to pursue your goals more effectively; that seems to be guaranteed. So you owe it to the world to be very concerned with what you do and whom or what you serve, even if it's yourself. The last thing the world today needs is one more kamikaze.

No comments:

Post a Comment